Munroe Bergdorf’s cardboard cutout personality successfully transfers onto page.

Introduction

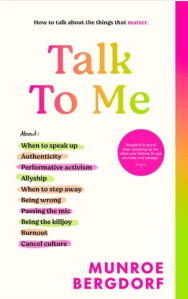

It’s been a big year for Munroe Bergdorf, as this Penguin how-to/self-help book called Talk To Me (how to talk about the things that matter) and the documentary Love & Rage: Munroe Bergdorf were released within days of each other, in June 2025. As of the date of writing, there is one review on Amazon, and, unusually, not a single endorsement embedded into the official blurb for the book. These people all have the same agent, so it’s not like there’s a dearth of Z-list slebs to gush over the truly inexecrable, therefore I suspect a marketing choice. The patronising Mother-knows-best tone makes clear it is aimed at younger teens (or else the mentally subnormal), though officially it is for those ‘aged 16 and up’. It is also clear from the factoids, a North American audience is sought.

Important context: Munroe Bergdorf is a Patron for Mermaids*, an honour bestowed on him during a Mermaids telethon in lockdown (April 2020) to incredible excitement. Naturally he mentions Mermaids several times in the book, signposting them and groups like Gendered Intelligence for further information.

*Patron count: Five out of six of Mermaids’ current Patrons are trans-identified males. All of the patrons transitioned as adults.

The principal aim of the book is to get young people involved in trans/far left activism using the current identity politic pyramid of oppression, whereby straight white middle class ‘cisgender’ men occupy the peak, so there are literally no surprises anywhere. Bergdorf also has a lot to say on ‘white supremacy’ but it is not the purpose of the review to cover that aspect.

Being trans is bringing who you truly are to the surface. What could be more beautiful?

Loc 2,117

The review

Contradictions

I read the whole thing and it’s a complete mess, but its repeated contradictions might be its worst fault. Totally over-egged, there are literally thousands of words on how Bergdorf does his activism, which are so trite. We learn that he educates himself by going to ‘debates, panels and book events’ (never seen him) (Loc 439), listening earnestly to all those he comes into contact with. And quite how many times we are lectured on having difficult conversations, I don’t know, but it must run into the dozens, only for the shutters to come thundering down, again and again. For example, in the section ‘Talking to a bigot’ (Loc 1,104), Bergdorf asks us to ‘consider the energy behind the words’ (Loc 1,125) in order to ascertain as to whether someone is worth engaging, and, if they don’t change their mind to ours, it’s better that we ‘decide to step away’ (Loc 1,169). I mean, I agree to some extent, given some of the fuckwits I’ve engaged with over the years, but having challenging conversations should alway be content over intent, surely?

Your community is comforting, but it should also challenge you – gently and in a way that makes you feel safe.

Loc 817, Talk To Me

We also learn that Bergdorf no longer accepts invites for television debates (Loc 1,286), which is fair enough, but this is a book about having difficult conversations, for fuck’s sake. Is he not a teeny-weeny bit embarrassed to admit this? Answer: Of Course Not. With regards to friends having a differing opinion, he is of similarly closed mind (reminding me that I will never forgive the Specials for Racist Friend), as he says this:

If someone is not willing to explore further with you why they think the way they think, then depending on how that makes you feel, you may need to let them go.

Loc 1,432

Again, this is a book supposedly encouraging young people to grapple with difficult subjects and people. How are any of them going to be talking to their mothers, bosses, colleagues, neighbours or, like, anyone if they follow this advice?

We are repeatedly told we can all do activism, but I feel an immature mind would feel dwarfed upon hearing about the debonaire activist life Bergdorf has carved out for himself had handed to him on a plate. Case in point:

Today, I can go to an event, dressed head-to-toe in couture, and talk about politics on the red carpet. I can spend a morning being silly and embracing my inner child, laughing with my friends, and then the afternoon shooting a documentary or preparing for a speech at a trade union conference or at a work-place where I’ve been hired to discuss trans rights and better practices for LGBTQIA+ employees.

Loc 573 in Talk to Me, under section headed – There’s only one you! Finding your authenticity

Another example of Bergdorf basically warning us of getting above our stations, is when he highlights the example of a meddling ‘cisgender person [who] wanted to organise a rally outside Downing Street’ (Loc 1,503) to protest single sex hospital wards. Bergdorf tells us he declined to take part in the protest because the person ‘formed their solution too quickly’ (Loc 1,519). However, it seems fairly obvious, reading between the lines, the real issues were that the ‘cisgender’ activist, A. Didn’t have the lived experience. And, B. Didn’t have the necessary gravitas to pull the stunt off (see A.)

Confusedly we are warned about ‘crafting an identity that feels more like a costume’ (Loc 586) whilst being advised on ‘personal branding’, i.e. to ‘defin[e] and promot[e] what you stand for as an individual’ (Loc 594), literally paragraphs apart. Meaning we never quite know where we stand with regards to this amazing activist journey Bergdorf is beckoning us towards.

I can host Queerphipany one day, talk at the UN the next, then go and advocate for trans kids before turning up on the red carpet in a full latex look. I’m multifaceted, and I can be all those things!

Loc 1,764 (Ghostwriter taking the piss.)

Red flag moments

Bergdorf tells us he was 24 years old when he began ‘medical transition’ and that: ‘This journey allowed the truth of who I was to come to the surface’ (Loc 253) (coming to the surface is a recurring theme). The point of telling us this, of course, is so that we can learn ‘how to examine who you are’ and ‘I’ll help you identify who your community are [sic]’ (Loc 260).

Bergdorf sneaked into a Soho nightclub aged 16 (Loc 689), where he learnt it wasn’t wrong ‘being camp and effeminate’ and then spends several pages praising the club known as PXSSY PALACE. (Set up so that black-queer-folx could have a safe space from white-cis-hets, natch.)

Whilst discussing Section 28, Bergdorf tells us that it was a ‘nonsensical idea that you could somehow stamp out a child’s sexuality by prohibiting them from having access to information or assistance’ (Loc 915).

In ‘Passing the mic’, Bergdorf tells us that he likes to ‘spotlight’ and ‘amplify the voices of transgender children’ (Loc 1,601) and refers to the activist group Trans Kids Deserve Better and the time they scaled an NHS building to protest the restriction of puberty blockers. What Bergdorf fails to mention, however, is that the Cass Report deemed puberty blockers unsafe, and instead repeats mantras about suicide risk, suicide ideation and that puberty blockers are ‘vital healthcare’ (Loc 1,610). Too scared to have difficult conversations he instead, with no irony or self-awareness whatsoever, moves onto ‘how to be a good listener, (yes, even to those who we think are wrong)’ (Loc 1,616) leaving no time to even mention claims about bone thinning and stunted brain development. Brave and stunning.

You can be someone who loves fashion and beauty, but who also wants to take a stand against the injustice in the world. […] Sometimes I wish I was more ignorant to a lot of injustice in the world […] But then I wouldn’t be living a life rooted in reality

Loc 1,729-1,736

He argues one of the motivating factors for the murder of Brianna Ghey was caused by media misgendering, leading to ‘dehumanization’, and that the murderous pair called Ghey ‘transphobic names’ (Loc 2,007). As per usual for the tragedy of Ghey’s murder, Bergdorf fails to mention that the two perps had fallen into the darkest places on the internet and that Ghey himself was similarly affected (a subject his mother has tacitly admitted and trying to address).

Bergdorf claims to have always known that he was ‘queer’, though never completely clarifies whether this means he always knew he was same sex attracted, or that he always knew he was trans. However, we learn that he ‘first came out to a childminder … around the age of seven’ (Loc 2,067) – why a childminder was happy to discuss sexual preferences with him is not expanded on. Section 28 is blamed for feelings of isolation, but the fact is he came out as gay to everyone aged 14.

I came to recognize my own power by thinking of activism as a machine. […] It’s just about finding which role you’re going to play.

Loc 380, Talk to Me

On feminism

Bergdorf pontificates on feminism, favouring, of course, the egalitarian/intersectional kind – ‘we all deserve equality’ – (Loc 465), while claiming that he has read the ‘feminist texts’ of ‘white middle-class/ upper class’ (Loc 499) women, like Germaine Greer. (According to Greer’s Wikipedia entry, her mother was a milliner and her father an advertising salesman, the family lived in rented accommodation. So, no silver spoon.)

There was also a possible glib reference to the situation affecting millions of women: ‘There are many places across the world where women are punished for how they dress’ (Loc 894). Clearly it was too difficult for a book on ‘how to talk about the things that matter’ to simply name Islam and mention a few of the Iranian women beaten to death for uncovering their hair. This is because trans activism, and far left activism in general, shares an axes with Islamic jihad; hence the almost zero condemnation of Iran’s anti-gay/pro-transition policies from the LGBT sector and intersectional feminism alike. If it were the Catholic Church meting out such religious punishments, there would no such leeriness.

On the law

Bergdorf tells us that workplace policies, rather than being based in law, are ‘created by a select few people at the top who could be carrying their own biases and prejudice’ (Loc 767). He also blames former PM Rishi Sunak of ‘pledging to rewrite the Equality Act … [so that] trans women would not be allowed to use women’s toilets’ (Loc 923).

Under existing law, transgender people are allowed to use the toilet that best matches their gender identity – so I can, legally, use a woman’s bathroom as I am a woman.

Loc 1,635

The copy may have been finalised before the FWS judgment was handed down but the publication date was still two months away, so the above lie could have been corrected.

Summing up

So, this definitely isn’t going to be a stocking filler come Christmas and I can only think that the two release dates were fused together because this book is so bloody terrible. On the plus side though, Bergdorf’s cardboard cutout personality has very successfully transferred onto page. An achievement of sorts then, which I give in full to the ghostwriter, clearly having too much fun at times. Bergdorf should stick to looking like a sex doll.

Thank you for reading! Sign up to my blog by going to the bottom of the page.

Please share on other forums if you liked it, as I only do Twitter.

You must be logged in to post a comment.